Highlands Biological Station

Dedication of the Sam T. Weyman Laboratory

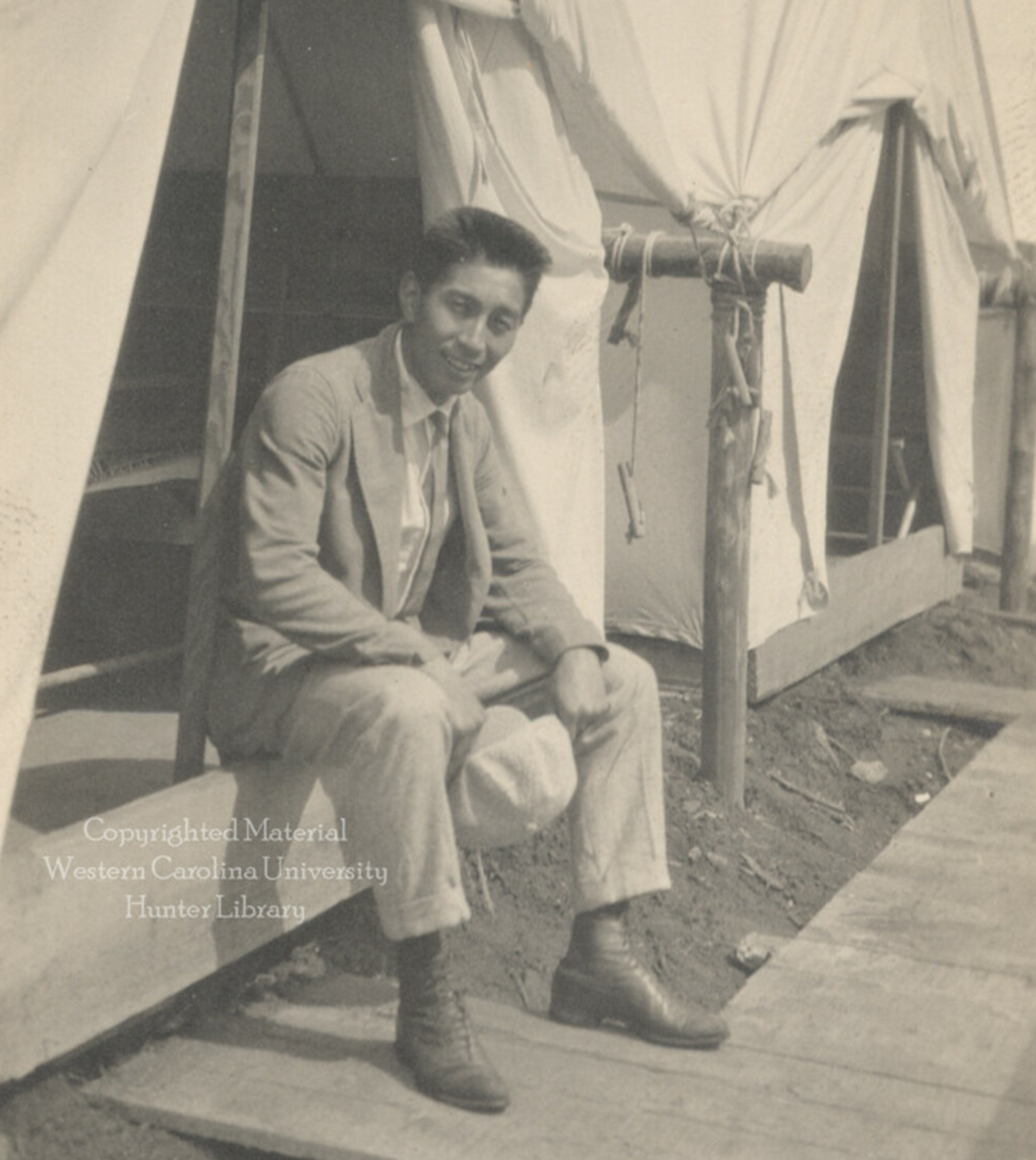

George Masa (circa 1890 – 1933), a Japanese immigrant and self-taught photographer, played a crucial yet often overlooked role in documenting the landscapes of the Southern Appalachians. Best known for his breathtaking black-and-white images of the Great Smoky Mountains—images that helped inspire the creation of the national park—Masa’s work extends beyond the Smokies and into Highlands, North Carolina. Among his lesser-known contributions is a photograph capturing the dedication of the Sam T. Weyman Laboratory at Highlands Biological Station. This rare image connects Masa’s legacy to the Station’s long history of ecological research and conservation. Through his lens, Masa preserved not just the grandeur of the mountains but also the moments and people dedicated to understanding and protecting them.

Click on each person in the photo below to learn more about their story and connection to Highlands Biological Station.

Sam T. Weyman Lab Dedication

This photograph, taken on August 29, 1931, captures the First Annual Meeting of the Highlands Museum and Biological Laboratory, held in conjunction with the dedication of the Weyman Memorial Laboratory in honor of Samuel T. Weyman.

Renowned photographer George Masa took the photo, likely commissioned by his friend and supporter, Frank Cook. Masa also captured three additional images of the building’s exterior. The original photograph is preserved in the Reinke Library Archives.

According to the Board of Trustees minutes:

"Samuel Nesbitt Evins read a biographical sketch of Mr. Weyman. Dr. Harvey Coxe, President of Emory University, delivered a dedicatory address, providing a historical overview of scientific education in the South and outlining the potential impact of the Laboratory's work."

The Highlands Marconian also recorded the attendance of Mr. Weyman’s widow, along with her sons, Fontaine and Samuel, and her daughter, Miss Betsey Weyman.

Since this inaugural meeting, the tradition of an Annual Meeting, featuring a yearly report on Museum and Laboratory activities followed by a Board of Trustees meeting, has remained a cornerstone of the Highlands Biological Station. Today, this tradition continues with the Highlands Biological Station Foundation.

Edith Eskrigge (1908 - 1986)

Edith Eskrigge was a member of the Highlands Museum and Biological Laboratory and was recorded as attending the August 1931 Annual Meeting. Born in England, she moved with her family to New Orleans in 1910. Edith and her family spent many summers in Highlands over the years. She graduated from Tulane University in 1933 and married Claude Wycliffe Haynes (1892–1989) in Highlands in 1942. From 1930 to 1934, Edith served as a trustee of the Museum. She is the mother of R.B. Haynes, a current supporter of Highlands Biological Station.

Albertina Staub (1866- 1942)

Born in Switzerland, Albertina Staub arrived in Highlands with her father around 1887, following the death of her mother from yellow fever during their overseas journey. Before settling in Highlands, they lived in Ohio, Savannah, and Atlanta, ultimately drawn to the area's mountain beauty and lack of mosquitoes.

Albertina was deeply involved in the community, serving as a trustee and librarian for the Highlands Library Association. She was also a founding member of the Highlands Museum and Biological Laboratory, where she held the role of secretary from 1927 - 1933 and was a trustee from 1927 to her death. She is recorded as attending the August 1931 Annual Meeting.

Throughout her years in Highlands, Anita served as postmaster and worked in real estate and the insurance business for approximately 25 plus years. Known affectionately by all as "Miss Staub," she was a well-respected and familiar figure in the community.

Mary Chapin Smith (Mrs. John Jay) (1855 - 1940)

Mary Chapin Smith and Albertina Staub, pictured together in the 1931 Masa photo, served as the Book Committee for the Hudson Library from approximately 1895, when the library was incorporated, for the next 40 years.

Mary Chapin, originally from Illinois and Massachusetts, arrived in Highlands in 1883 and married J.J. Smith in 1886. Their home, now known as the Highlands Inn, was a wedding gift from her aunt, Eliza Wheaton, founder of Wheaton College. Both Mary Chapin and Albertina were present at the founding meeting of the Highlands Museum in August 1927. They became trustees and remained actively involved with the Museum and Laboratory for many years.

J.J. Smith was an entrepreneur, road and bridge builder, and woodsman, while Mary Chapin was a poet and artist, known for painting botanical illustrations for renowned botanist Asa Gray. She was also a founding member of the Highlands Improvement Society (now the Highlands-Cashiers Land Trust) in 1904 and was actively involved in floral and horticultural societies.

Additionally, the Smiths were members of the Mineral Society, founded by the Museum, and in 1930, they donated their mineral collection largely from Macon County to the Museum, further enriching its scientific and educational resources.

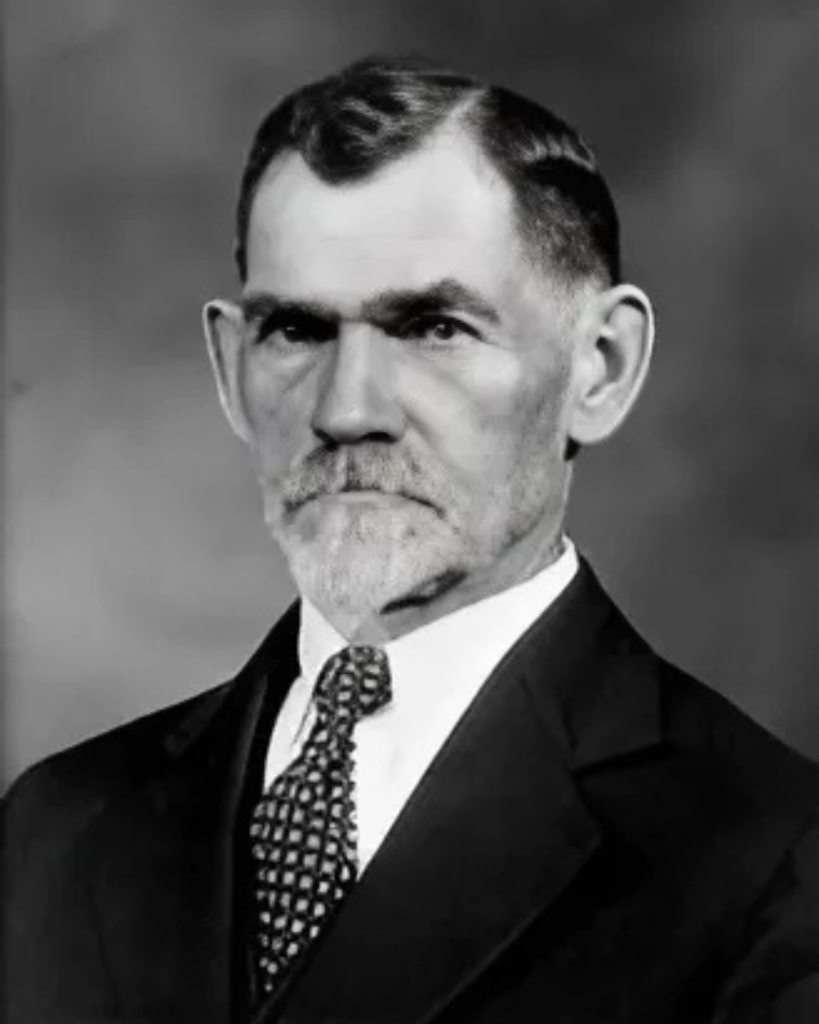

Samuel Nesbitt Evins (1871- 1939)

Sam Evins was born in Spartanburg, South Carolina, in 1871. He attended Wofford College and the University of South Carolina before earning his law degree from Harvard University in 1893. Moving to Atlanta in 1894, he built a distinguished legal career, first with the firm King and Spalding law firm and later with Jones, Evins, Moore, and Powers.

He and his wife, Mary Elliott Moore of Columbia, South Carolina, had two sons, Thomas A. Evins and Samuel Nesbitt Evins Jr. Beyond his legal work, Evins was an active civic leader, serving on the Atlanta City Council and the Atlanta Board of Education. A close friend of Samuel T. Weyman, he spoke about Weyman’s life and character at the dedication of the Weyman Laboratory.

Dr. Edwin Eustace Reinke (1886 - 1945)

Dr. Reinke was born to American parents in Jamaica and pursued his education at Lehigh University, later earning his doctorate in cytology from Princeton University in 1913. He joined Vanderbilt University in 1915 and became a full professor of biology in 1922, with a strong focus on advancing pre-medical education. Among his nationally recognized research projects was his experimental work in the field of hormones.

A founder and lifelong supporter of the Highlands Museum and Biological Laboratory, Dr. Reinke served as its director from 1929 to 1935. In 1929, he authored the institution’s first publication, Report on the Necessity of a Mountain Research Laboratory in the South. In his honor, the Reinke Library was established to house biological and research papers.

Dr. Reinke, his wife, Emily A. Feuring (1887–1934), and their two daughters spent summers in Highlands at their home—a Joe Webb cabin located two blocks from the Highlands Biological Station—which is now the site of the Highlands Hiker store.

Dr. William Chambers Coker (1872 -1953)

Dr. Coker, born in Hartsville, South Carolina, developed a passion for nature from an early age. He attended the University of South Carolina in 1891 and earned his doctorate from Johns Hopkins University in 1901. Joining the biology faculty at the University of North Carolina in 1902, he remained there until his retirement in 1945. An avid explorer of the region’s rich botanical diversity, he authored 137 publications on flora, fauna, and fungi. A man of many honors, he also established the Coker Arboretum, featuring a collection of primarily native shrubs and trees.

A founder of the Highlands Biological Station (HBS), Dr. Coker served as its director from 1936 to 1943 and as director of the Laboratory from 1936 to 1944. Upon his passing, the 1945 Annual Meeting records noted: “In addition to carrying on his official duties and scientific research at the Station, Dr. Coker became a generous contributor as a donor of finance and property. During his many summer residences, he found inspiration and relaxation in the mountains.”

Dr. Coker and his wife, Louise Manning Venable, bequeathed the Coker Rhododendron Trail to HBS, a cherished landmark that still preserves some of the old-growth forest trees found in Highlands today.

Clark Howell Foreman (1902 - 1977)

Clark Foreman, for whom today’s Nature Center was originally named—the Clark Foreman Museum—was a member of the Howell family of Atlanta, who owned property in Highlands and spent summers there. He played a pivotal role in the founding of the Highlands Museum and Biological Station, persuading Dr. Reinke and Dr. Coker to pursue biological research in the region.

Foreman had a distinguished career in public service, serving in the U.S. Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C., and as Director of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). He was also an advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Southern policy, the founder and president of the Southern Conference on Human Welfare, and the director of the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee from 1951 to 1968. A first-generation civil rights activist, he dedicated much of his life to social justice.

In his later years, Foreman returned to Highlands, where he spent the last decade of his life as a full-time resident.

Frank Benjamin Cook (1892 - 1980)

A native of Greenwood, South Carolina, Cook was a realtor and insurance agent in Highlands. He and his wife, Verna Holbrook, owned the Highlands Inn, where his offices were located for 55 years.

A strong supporter of photographer George Masa, Cook invited him to Highlands in 1929 to capture images of the area for promoting the Inn. He likely brought Masa back to document the opening of the new Weyman Laboratory and the inaugural Annual Meeting of the Highlands Museum and Biological Laboratory in August 1931.

Nathan Billstein (1859 - 1931)

Nathan Billstein was a master printer in Baltimore, associated with The Lord Baltimore Press from 1906 until his retirement in 1922. (The press later became part of International Paper in 1970.) He married Ella Lillian Myers in 1894, and together they had two daughters.

His sister, Dr. Emma L. Billstein (1855–1914), was an accomplished physician who earned her medical degree from the Woman’s College of Pennsylvania and conducted research in cellular dispersal. She owned property in Highlands as early as 1903, which Nathan inherited upon her passing. Dr. Emma Billstein was also the first president of the Highlands Improvement Society, now known as the Highlands-Cashiers Land Trust.

Nathan Billstein attended the August 1931 Annual Meeting of the Highlands Museum and Biological Laboratory, answering the roll call. He passed away in November of that year.

Dr. Harvey Warren Cox (1875 - 1944)

Dr. Cox served as president of Emory University from 1920 to 1944, a period of substantial growth for the institution. He was the keynote speaker at the opening of the Weyman Laboratory, where he praised the institution as a “pioneer in the South in making beaten paths in education.” He envisioned the laboratory fostering greater collaboration among Southern institutions and contributing to regional academic advancement.

A northerner by birth and education, Cox asserted that the South was no longer sectional and predicted significant progress in both education and industry. Under his leadership, Emory University became one of the original institutional members of the Biological Laboratory.

Dr. Burnham Standish Colburn (1872 - 1959)

Dr. Colburn, originally from Michigan, was a banker, bridge builder, historian, and real estate developer. He moved to North Carolina in the 1920s and played a key role in organizing the Biltmore Estate Company, serving as its vice president and treasurer until 1936. He later became president of the First National Bank and Trust Company in Asheville, retiring in 1953. Under his leadership, the bank eventually merged with Union Bank of North Carolina to become First Union National Bank of North Carolina.

A passionate mineral enthusiast, Colburn was instrumental in founding the Southern Appalachian Mineral Society, having roamed his father's large iron mine as a child. His extensive mineral collection became the foundation of the Burnham S. Colburn Memorial Mineral Museum, now part of the Asheville Museum of Science. Additionally, he assembled a significant collection of Cherokee artifacts, which was later sold to Samuel Beck of Asheville and is now housed at the Museum of the Cherokee People in Cherokee, North Carolina.

Just before the dedication of the Weyman Laboratory, the Trustees of the Highlands Museum and Biological Laboratory elected Colburn as President, a role he held for two years. In 1937, he donated a portion of his mineral collection to the Museum and became a regular lecturer on minerals during the summer sessions.

Dr. Edward Sturtevant Hathaway (1886 - 1984)

Dr. Hathaway was born in Tennessee and earned his doctorate in zoology from the University of Wisconsin in 1925. He went on to become a professor at Tulane University, where he gained recognition as the "Father of Louisiana Mosquito Control." In 1952, he was appointed chairman of the Zoology Department, a position he held for 26 years.

Throughout his career, Dr. Hathaway was honored for his scientific contributions, though he found particular amusement in 1952 when the Louisiana crayfish, Orconectes difficilis hathawayi, was named in his honor. His 1959 publication, Key Recognition of Louisiana Mosquitoes with Naked Eye and Hand Lens, became an essential training tool for Louisiana entomologists.

Dr. Hathaway was an active member of the Highlands Museum and Biological Laboratory, answering the roll call at the August 1931 Annual Meeting and previously attending the 1930 meeting, where he advocated for the establishment of a mountain research laboratory. He served as a trustee until 1938.

Benjamin "Bennie" Bruton Fontaine Weyman (1870 - 1957)

Bennie was the widow of Samuel Thompson Weyman, for whom the Weyman building was named. She married Sam Weyman in 1900, and together they had four children: George Fontaine Weyman (1901–1958), Samuel Maverick Weyman (1903–1982), Fontaine Bruton Weyman (1912–2005), and Elizabeth (Betsy) Weyman Yearley (1913–2011). Born in Columbus Georgia, Bennie was 59 years old when her husband Sam died in a forest fire on their property in Atlanta in 1929.

Dr. Thomas Grant Harbison (1862 - 1936)

Dr. T.G. Harbison was an American botanist originally from Pennsylvania who moved to Highlands in 1886 to serve as the local school principal. From that point forward, he considered Highlands his home, despite residing and working in various locations throughout his career. He remained involved in local education until 1896, after which he pursued a distinguished botanical career.

From 1897 to 1903, Harbison worked as a plant collector for the Biltmore Herbarium. He then served as a field botanist for Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum from 1905 to 1926, specializing in the collection of woody plants. In his later years, he collaborated with William Willard Ashe (1872–1932) on Ashe’s extensive herbarium collection. After Ashe’s passing in 1932, Harbison and W.C. Coker worked together to secure and catalog the collection for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In 1934, he was appointed curator of the herbarium, a position he held until his death.

In 1896, Harbison married Jessamine “Jessie” Margrit Cobb (1868–1954) in Highlands, where they raised four children. The couple remained in Highlands for the rest of their lives and are buried in the local cemetery.

Harbison played a significant role in the Highlands Museum and Biological Laboratory, contributing to its development over many years. In January 1931, he authored Publication No. 3: A Preliminary Check-List of Ligneous Flora of the Highlands Region, North Carolina.

Harris Lake, as it is known today, was originally called Harbison’s Lake in recognition of his contributions

John Pierce Anderson (1907 - 1999)

John P. Anderson was the son of Dr. Alexander P. and Lydia Anderson, and spent most of his life in Red Wing, Minnesota. His sister, Louise, married Ralph Sargent, and both families spent summers in Highlands for many years. (See the February 2025 HBS newsletter for more on the Anderson and Sargent families.)

As recorded in the minutes of the August 29, 1931, meeting: “Dr. Alexander P. Anderson was represented by his son, John P. Anderson.”

John attended the University of Chicago and the Yale University Art School. An artist and independent scholar, he pursued a diverse career in photography, woodworking, and metal craftsmanship. In 1930, he married Eugenie Moore, who later served as a United States diplomat from 1949 to 1968. Together, they traveled extensively, creating a significant photographic record of people and architecture across many countries.

Possibly George Fontaine Weyman (1901 - 1958)

Fontaine Weyman was the first son of Samuel T. Weyman and Benjamin Bruton Fontaine Weyman. He attended the University of Virginia and married Mary Ann Lipscomb (1906-1987) in 1925. Their first child, Anne Weyman, was born in 1927 and may be the child pictured sitting on his lap.

Fontaine, along with his siblings Samuel Maverick Weyman and Betsy Weyman, was recorded as being present at the dedication of the Weyman Laboratory.

Possibly Albert Comer Howell Jr. (1904 - 1974)

Albert Howell was the son of Clark Howell, editor of The Atlanta Constitution. He earned his degree in architecture from Columbia University in 1928 before spending a year in Europe studying architecture in France and Italy.

In 1929, Howell partnered with McKendree Augustus Tucker (1895–1972) to establish the architectural firm Tucker & Howell in Atlanta. Together, they generously contributed their time, along with Philadelphia architect Oscar Stonorov, to the design of the Samuel T. Weyman Laboratory.

Frank Hamilton Brown, Sr. (1883–1965)

Possibly Dr. A. S. (Arthur Seaver) Wheeler (1864-1937)

Dr. Wheeler was born in New Orleans and earned his Doctorate in Veterinary Medicine from the University of Pennsylvania around 1922. He married Anna Grant Norton in New Orleans in 1889. Around 1897, the couple moved to Biltmore Forest in Asheville, where Dr. Wheeler served as both Manager and Veterinarian.

Mary Elizabeth (Betsy) Weyman Yearly (1913 - 2011)

Betsy was the daughter of Samuel T. Weyman, for whom the building is named. She spent most of her life in Atlanta and married Alexander Yearly IV of Baltimore, Maryland, in 1936. Betsy had two daughters, Fontaine Yearly Draper and Helen Yearly Durant, who have generously assisted us with family identification.

Samuel Maverick Weyman (1903 - 1982)

Sam was the second son of Samuel T. Weyman, for whom the building is named. He spent most of his life in Atlanta, where he worked in the family’s insurance and real estate business.

Author’s Notes

Randolph Shaffner’s Heart of the Blue Ridge: Highlands, North Carolina and Ralph Sargent’s Biology in the Blue Ridge have been invaluable resources for the biographies included in this historical analysis.

The women in this photograph remain largely unidentified—not intentionally, but due to the difficulty of recognition caused by their hats.

Note: This interactive photo is a work in progress. If you notice anyone who may be misnamed or recognize someone who isn’t yet identified, please don’t hesitate to reach out to us at hbs@wcu.edu.

Special thanks to Bryding Adams, Sarah Vickery, and Katie Cooke for their work compiling and presenting this project!