Highlands Biological Station

From Obscurity to Exhibit

From Obscurity to Exhibit: Highlands’ Mineral Treasures Resurface

HIGHLANDS, N.C. — In a storage room on the edge of a mountain campus, the rocks were waiting to tell their stories.

Sarah Vickery, University Program Associate

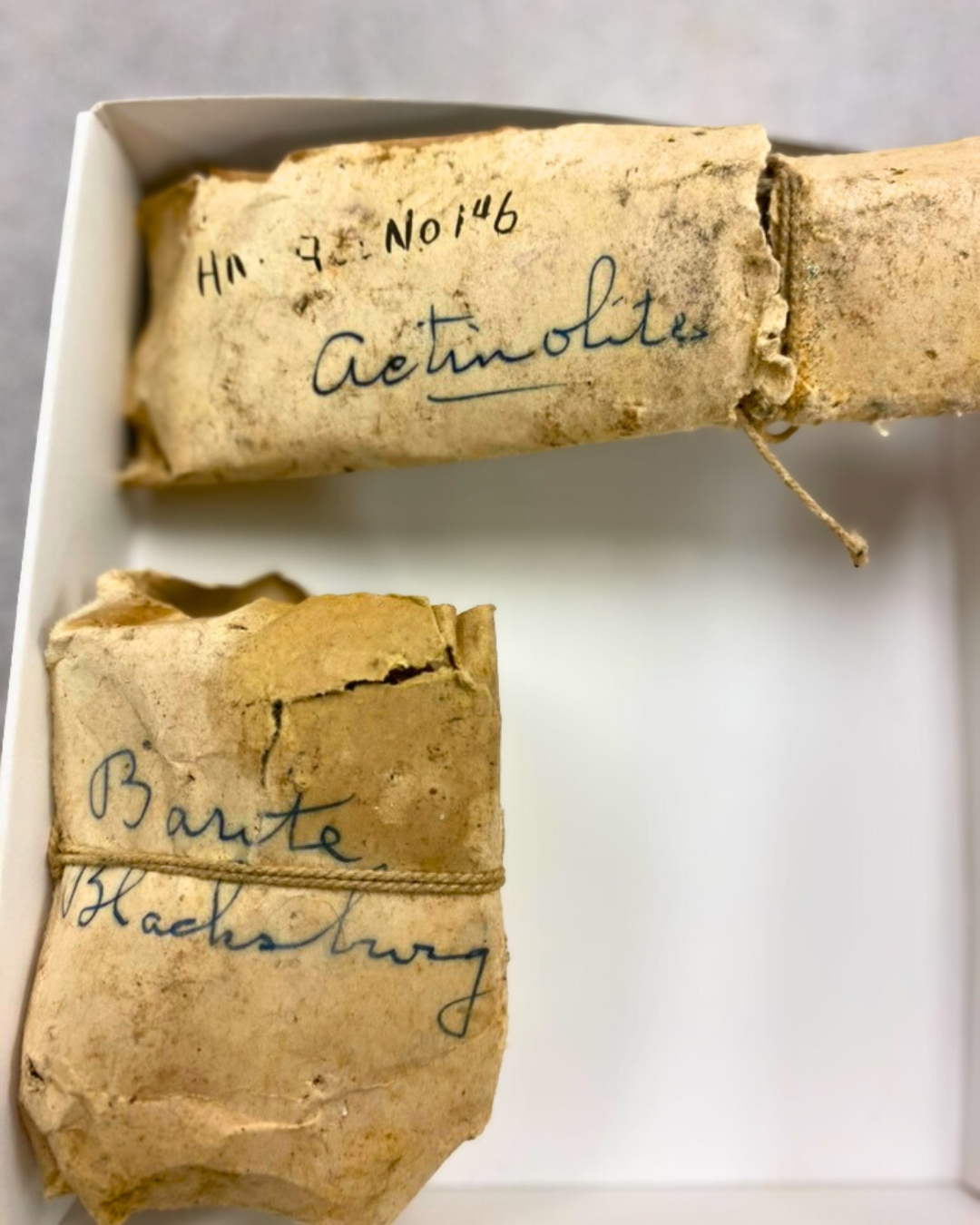

Packed in cardboard boxes and plastic tubs—some labeled in fading ink, others stripped of identity—the minerals had slipped into obscurity. Once treasured donations, they included quartz and emeralds from the Blue Ridge, candle quartz from Russia, and Herkimer diamonds from New York. By the time Western Carolina University geology students Kaley Shoffner and Sophia Platt—guided by professors Cheryl Waters-Tormey and Shane Schoepfer—opened the boxes last summer, the collection had become more rumor than resource.

“I thought maybe 50 to 100 rocks,” Kaley said. “Instead, it was thousands.”

For Sophia, the surprise was the quality. “You had specimens from all over the world that were just in boxes,” she said. “Some of them were museum-grade.”

Their job—cataloging the collection—uncovered not only minerals but a forgotten chapter of Highlands Biological Station’s history, one that will soon take center stage as the Station approaches its 2027 centennial.

The Mission in the Mountains

Founded in 1927, the Highlands Biological Station sits at 4,000 feet in the southern Blue Ridge, one of the world’s great biodiversity hotspots. Now a multi-campus center of Western Carolina University, its mission is to foster research, education, and conservation tied to the region’s natural heritage.

From its earliest years, the Station attracted scientists and summer residents. Its moss gardens, pitcher plant bogs, and lake-edge labs became classrooms for generations. But curiosity extended beyond flora and fauna. In 1930, the Station received the J. Jay and Mary Chapin Smith Collection, one of its first significant mineral donations. A generation later, between 1969 and 1973, the Harold B. Mallory Collection expanded the Station’s holdings even further.

By mid-century, a surge of community enthusiasm gave rise to the Highlands Mineral Society. Founded in 1955, members combed ridges and creek beds for crystals, corundum, and sapphires. Between 1955 and 1962, their donations swelled the Station’s mineral cabinets.

Old donor cards, tucked among the stones, preserve that mid-century fervor. “Whoever made the catalog had a very specific handwriting,” Sophia said. Connecting cards to specimens felt like restoring credit. “It was like a breath of fresh air—honoring the people who made the donations.”

Two Young Geologists, Two Paths

Kaley didn’t begin in geology. After earning an associate’s degree in accounting, she realized office life wasn’t for her. “I want something more hands-on and applied,” she said. Childhood memories of microscopes and mountains led her back to geology, where she fell in love with mineralogy.

Sophia’s route was more direct. Growing up in Florida, she collected rocks and dreamed of the mountains. Drawn to WCU’s geology program, she embraced structural geology and now hopes to pursue a Ph.D. After graduation, she may spend a year in Asheville working in landslide consulting.

The Highlands project united them. Three weeks in the Coker Lab, armed with an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, they sorted minerals, grouped specimens, and built a digital catalog. “It was tedious,” Sophia admitted, “but also rewarding. When you identify something correctly, it’s an aha moment.”

Treasures and “Back to Nature Rocks”

What they found ranged from the ordinary to the extraordinary. Some stones—pretty but lacking scientific or teaching value—were returned to the earth. Others stunned even seasoned eyes: spessartine garnets from Russia, corundum and sapphires from North Carolina’s mining past, and a brilliant blue quartz still tagged with its price.

For Kaley, discovering local emeralds was a revelation. “It showed me the mountains are much more diverse mineralogically than I expected.”

Together, they recommended two displays: one of native Blue Ridge specimens, another of international crystals. “If you put local gneiss next to a massive crystal, one shines more to the average eye,” Sophia explained. “Separating them makes sense.”

Hurricane Helene and the Living Mountains

Geology became even more urgent last fall when Hurricane Helene struck western North Carolina. Torrential rains triggered landslides that cut off communities.

“I’m from Florida, so I never experienced landslides,” Sophia said. “Seeing whole towns cut off was very impactful.” Now she’s working on a project in Chimney Rock studying slope failures. Before graduate school, she hopes to help communities prepare for such risks.

Kaley, too, is drawn to applied geology. She’s applied to ECS Southeast in Asheville to work on construction and disaster remediation. “It feels like a very important job to do right now,” she said.

Toward the Centennial

As the Highlands Biological Station nears its 100th year, its mineral collection offers both a look backward and a step forward. Donor cards, local crystals, and Russian specimens will shape new centennial exhibits.

Kaley and Sophia recommended display pieces from Herkimer diamonds to massive crystal specimens. “We were like, this has to be showed off,” Kaley said. Sophia imagines displays as art, incorporating vegetation and local flora for context.

For the Station, the project is about legacy. Just as the Mineral Society reflected postwar citizen science, Kaley and Sophia’s work embodies a new generation shaped by both curiosity and climate change.

“This was a great opportunity,” Sophia said. Kaley agreed: “It was fun.”

The rocks, once forgotten, are cataloged now, their stories reattached to names and places. They will soon have their moment under glass as the Highlands Biological Station marks its centennial—reminders that even the oldest stones can speak to the present.

Funding Acknowledgment

This project was made possible through the generous support of the Highlands Biological Foundation, which provided funding—via a gift from Dick Goodsell in memory of Claude Sullivan—to hire students to catalog and preserve the Highlands Biological Station’s mineral collection.

Their work ensures that these specimens, once tucked away in storage, are reconnected with their history and shared with the public as part of the Station’s 2027 centennial celebration.