Highlands Biological Station

Dr. Lindsay Shepherd Olive: A Life in Mycology and Conservation

Lindsay S. Olive as a University Student c. 1940

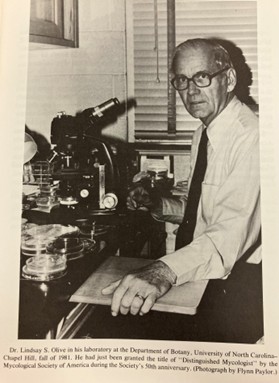

Lindsay Shepherd Olive was born on April 30, 1917, in Florence, South Carolina. Over the course of a remarkable career, he became a professor at Columbia University and the University of North Carolina, a Distinguished Mycologist of the Mycological Society of America, and a Fellow of the National Academy of Sciences. His legacy includes decades of service to the Highlands Biological Station, where he served on the Conservation Committee and the Highlands Botanical Garden Committee as Chairman beginning in 1947.

Dr. Olive was the eldest of three children and was raised on a farm near Apex, North Carolina, with his brother and sister. He earned a scholarship to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. As an undergraduate, he enrolled in the graduate mycology course taught by Professor John Couch. Deeply influenced by Couch’s passion for the subject and engaging teaching style, Lindsay decided to devote his life to mycology. He earned his B.A. in 1938, M.A. in 1940, and Ph.D. in 1942, all from UNC–Chapel Hill.

In 1938, Olive first visited Highlands, North Carolina, with Professor William Chambers Coker. He quickly fell in love with the region and returned as often as he could. His thesis and dissertation, under the mentorship of Professors Couch and Coker, focused on nuclear and life-cycle phenomena in rust fungi.

During this period, Olive met Anna Jean “Jeannie” Grant, a fellow student from Chapel Hill who had grown up in Murphy, not far from Highlands. They married in Highlands on August 28, 1942, shortly after he received his doctorate.

Olive began his teaching career as an instructor in the Botany Department at UNC. In 1944, during World War II, he joined the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Beltsville, Maryland, as a mycologist and plant pathologist. The government, concerned about threats to critical crops, had mobilized scientific resources to prevent potential biological attacks. Although Olive published several papers on plant diseases affecting soybeans, cowpeas, and sorghum, plant pathology was not his true passion.

After a brief appointment at the University of Georgia, where his teaching load left little time for research, Olive moved to Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. He remained there for three years until 1949, when he accepted a position as associate professor of botany at Columbia University in New York. While at Columbia, he authored a landmark article in Botanical Review in 1953 titled “The Behavior of Fungus Nuclei.”

In 1956, Olive received a Guggenheim Fellowship to study jelly fungi in the Society Islands. His proposal caught the attention of Senator William Proxmire, known for mocking what he viewed as frivolous research. Nevertheless, the project proved fruitful and led to numerous publications, effectively launching Olive’s second career in tropical mycology. Olive and Jeannie traveled extensively—to Europe, Africa, New Zealand, Australia, Southeast Asia, and many Pacific islands—always searching for new fungal species, and finding many.

In New York, Olive became active in the scientific community through the New York Academy of Sciences, the Torrey Botanical Club, and the New York Botanical Garden. There he befriended Donald P. Rogers, curator of fungi, and became acquainted with Bernard Ogilvie Dodge, an expert on Neurospora. Inspired by their work, Olive developed a research program with the related genus Sordaria. With the help of his postdoctoral students, he transformed Sordaria into a powerful genetic system widely used in botany, mycology, and genetics to illustrate inheritance using ascospore color and shape as markers. This system became a staple of genetics and mycology instruction, and Olive was instrumental in its development. In his final years at Columbia, he served as President of the Mycological Society of America.

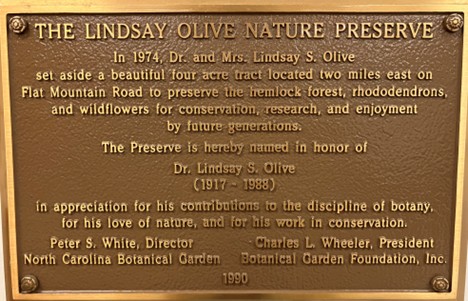

During these years, the Olives spent their summers in Highlands, where they built a cabin in 1947 on a scenic piece of land on Bowery Road. Enchanted by the site—with its mature rhododendron thickets and towering hemlocks—they later donated it to The Nature Conservancy. The property is now owned by the Highlands-Cashiers Land Trust. They then purchased another nearby parcel with a spectacular view for their retirement home.

By the late 1960s, institutional changes at Columbia and the New York Botanical Garden led Olive to accept a professorship at his alma mater, UNC–Chapel Hill. In 1968, he was named a University Distinguished Professor and honored as a Distinguished Mycologist by the Mycological Society of America, alongside his beloved mentor, John Couch. He also began work on what would become his major monograph, The Mycetozoans, published in 1975.

The Highlands Botanical Garden and Conservation Work

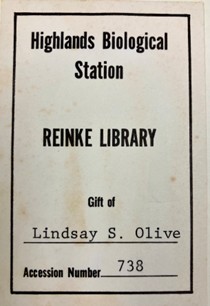

Beginning in 1950, Olive published numerous works on fungi resulting from his research at the Highlands Biological Station. A prolific scholar, he authored around 160 scientific papers and described many new fungal species—seven of them in his final ten papers. He gave a lecture titled “Tahiti” in 1957 and talks on mushrooms in 1964 and 1965. All the while, he worked diligently on the grounds of the Botanical Garden. Dr. Olive was also a generous donor to the E. E. Reinke Library, contributing more than 60 books from his personal collection and all of his published papers to support future researchers at the Station.

In 1967, Olive became Chairman of the Botanical Garden Committee, giving him a central role in shaping the Garden’s development. That same year, he delivered a lecture titled “Fungi Around Highlands.” In 1968, he received a Citation of Merit for his service—a turning point year for the Garden. Olive and Ralph Sargent began regular garden tours, personally donating and planting native species themselves.

Olive was also involved in broader institutional planning, becoming a Station Trustee in 1971. In 1972, he joined an ad hoc committee to negotiate the affiliation of the Highlands Biological Station with the University of North Carolina. The committee was empowered to recommend changes to the corporation’s by-laws as needed.

In 1973, under Olive’s direction, William Floyd collected both representative and rare plants of the southern mountains. Dr. Dorcus Brigham and Margaret Ballard Crumpler developed an herb garden adjoining the native plant collection. By 1974, seventy additional species had been added to the Garden, bringing the total to 465 native species and 56 varieties in the herb garden.

Olive also worked closely with Henry Wright, a knowledgeable local naturalist and amateur botanist, spearheading efforts to preserve rare flora in the region. Together, they helped identify and protect research tracts on Chestnut Ridge, Scaly Mountain, and Buck Creek. These efforts culminated in 1975, Highlands’ centennial year, when the U.S. Forest Service formally designated five tracts as Nature Study Sites. These sites—chosen, evaluated, and recommended by members of the Conservation Committee, including Wright, Olive, Dan Pittillo, and Ralph Sargent—were:

- Piney Knob Fork on Scaly Mountain (32 acres)

- Walking Fern Cove, Buck Creek (17 acres)

- Kelsey Tract, Chestnut Ridge (120 acres)

- Cole Mountain, west of Shortoff (56 acres)

- Bryson Creek, Ellijay Road (16 acres)

The Conservation Committee also supported the Forest Service’s decision to designate the area around Lower Cullasaja Falls as a scenic area, preserving it from tree cutting.

In 1976, when severe storms flooded the Botanical Garden, Olive led the recovery efforts—rebuilding bridges, clearing paths, and restoring plantings. That same year, he joined the inaugural Board of Scientific Advisers of the newly restructured Highlands Biological Station, chaired by Dr. Joseph R. Bailey of Duke University.

In 1979, Olive developed the Master Plan for the Henry M. Wright Preserve, which Wright later donated to The Nature Conservancy in 1986. The preserve is now owned by the Highlands-Cashiers Land Trust.

Final Years and Legacy

After retiring from UNC in 1982, Olive and Jeannie moved permanently to Highlands, where he maintained a research room at the Biological Station until 1986. Many of his students had conducted field research in Highlands, linking Olive to a four-generation genealogy of mycology at the Station. His ideal retirement consisted of six months in Highlands and six months somewhere warm. He became affiliated with the University of Hawaii, where he had previously served as a visiting professor in 1963 during a sabbatical from Columbia University, and continued his research there for several winters.

Sadly, his final years were marked by a decline due to Alzheimer’s disease. He closed his laboratory and remained at home under Jeannie’s care until his death at Highlands-Cashiers Hospital on October 19, 1988. When Jeannie passed away on December 25, 2005, the couple—having no heirs—left a substantial bequest to the Highlands Biological Foundation to fund student research scholarships. They are both buried at Highlands Memorial Park.

Personal Remembrances by the Author

Dr. Olive and Jeannie were central figures in the Highlands community. They had a vibrant social life, often enjoying cocktails and bridge with friends—including Frank and Lois Dulany, the grandparents of this writer. I remember Dr. Olive fondly from my childhood summers in Highlands. Once, I found a penny nailed to the floor of the front porch at his cabin—a prank he and Jeannie laughed heartily about. Another time, he took my brother, Key Compton, and me boating on Lake Sequoyah and showed us how to blow bubbles through a lily stem. We’ve never forgotten how close he steered his boat to the edge of the dam!

When I was in sixth grade, I was fortunate to spend two weeks traveling through the Smoky Mountains with my grandparents, Dr. Olive, Ralph Sargent, and Clermont Lee. At each overlook, he would step to the edge (where there was a lower ledge I couldn’t see) and pretend to fall—only to pop back up laughing. He was always full of surprises.

Dr. Lindsay Olive’s legacy endures not only in academic circles but also in the forests and gardens he loved. His life was a rare blend of scientific brilliance, humor, and deep curiosity.

References

Information on Olive’s life and career was drawn largely from files in the E. E. Reinke Library at the Highlands Biological Station (1947–1986), spanning his tenure with Executive Director Thelma Howell through his resignation, and from two articles by his former student, Dr. Ronald H. Petersen, Department of Botany, University of Tennessee:

- Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society, Summer 1981, pp. 70–76

- Mycologia, “Lindsay Shepherd Olive, 1917–1988,” 1989, pp. 497–503

Author:

Holly Compton Shields is the granddaughter of Frank and Lois Dulany (see Notes from the Archives, HBS online newsletter, July 2025, “Franklin Reed Dulany, Sr. 1897–1982”). Holly and her brother, Key Dulany Compton, spent their childhood summers in Highlands with their grandparents and remain summer residents today. Holly is an active volunteer in the HBS Archives.

– Holly Compton Shields, Volunteer Archivist, November 2025