HIGHLANDS BIOLOGICAL STATION

The Legacy of Margaret Ashley Towle

Margaret Elizabeth Ashley Towle (1902–1985)

Archaeologist and Ethnobotanist

Biography, Education, and Early Career

Margaret Elizabeth Ashley was a celebrated archaeologist in Georgia during the late 1920s. She conducted extensive research on Indigenous peoples across the state, work detailed by Frank T. Schnell Jr. in Grit-Tempered: Early Women Archaeologists in the Southeastern United States (1999). Her chapter is titled “Margaret E. Ashley: Georgia’s First Professional Archaeologist.” (Margaret and Schnell’s father worked together at the Neisler site near the Flint River for three weeks in October 1928.)

Born in Atlanta on January 12, 1902, to city councilman Claude Lordawich Ashley and Elizabeth Miller, Margaret graduated from Oglethorpe University in 1924 with a degree in English and journalism. She earned her doctoral degree in anthropology from Columbia University in 1929. During her summer field seasons, she worked at archaeological sites throughout Georgia, beginning in June 1926 at the Shinholser site in Baldwin County. By July 1927 she had begun her master’s thesis, “An Archaeological Survey of Georgia,” documenting approximately 500 known Indigenous sites.

In September 1927, the president of Emory University invited her to organize a new Department of Archaeology and to represent the university in Warren K. Moorehead’s excavations at the Etowah Indian Mounds near Cartersville, Georgia. Because Emory contributed financially to the project, part of the resulting collection would be housed at the university. Margaret accepted and left Columbia. In December 1927 Moorehead wrote that she would soon take over the excavation, praising her as “a very competent, trained, and brilliant young woman who is ready to step in.” While working at Etowah, she visited at least twelve additional Indigenous sites across North Georgia.

Local newspapers closely followed the Etowah excavations. A March 27, 1927 Atlanta Constitution article titled “Early Georgian Tribes Linked With Maya Indians of Mexico” expressed hope that Margaret—“Atlanta girl… who will obtain her doctor’s degree this year at Columbia”—would continue Moorehead’s work. On March 18, 1928, the paper reported on excavations at the Carter’s Quarters mound, noting: “The party of archaeologists, including Miss Margaret Ashley of Atlanta, has been exploring the Carter’s Quarters mound for the past week… Gerald Towle, field assistant to Dr. Moorehead, has been responsible for much of the success of the Georgia mound explorations.”

A May 8, 1932 the Atlanta Constitution article about Moorehead’s Etowah Papers (Yale University Press) listed both Gerald Towle and Margaret Ashley as assistants. It also noted that “Mrs. Towle contributed a paper of observations on the ceramic art of the Etowahs,” describing locally sourced clays capable of firing to multiple colors. Curiously, Gerald Towle was not listed among the volume’s authors.

Today, the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University still houses the Art of the Americas collection excavated by Moorehead, Towle, and Ashley.

Photograph of Margaret Ashley at the Etowah, Georgia archaeological site in 1928, restored in 2022. In the right background is a slightly out of focus image of archaeologist Warren Moorehead. Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology 2020.3.283

Margaret E. Ashley standing on top of the Hartley-Posey Mound, 9Tr12, October 1928. (Photo courtesy of the Columbus Ledger Enquirer.)

Margaret Ashley and The Highlands Museum

Margaret Ashley was among several young women who conducted research and curation work at The Highlands Museum and Laboratory during the 1920s and 1930s. Many received stipends to support their living expenses while living and working in Highlands, North Carolina.

At the August 14, 1927 Trustees meeting, William B. Cleaveland Jr. offered to sell his collection of Indigenous artifacts to the newly formed Museum for $1,000. Clark Foreman noted that the collection “would be the nucleus” of a growing natural history museum. The Trustees approved the purchase and commissioned a one-room addition to the Library Building, completed during the winter of 1927–1928. The Museum opened on July 4, 1928.

On February 17, 1928, Foreman wrote to Margaret inviting her to spend several weeks at the Museum that summer: “We are anxious to have an archaeologist who is acquainted with the Indian history. The region, though archaeologically fertile, is I believe practically unworked.” He invited her to stay at his family’s summer home. She accepted on March 7.

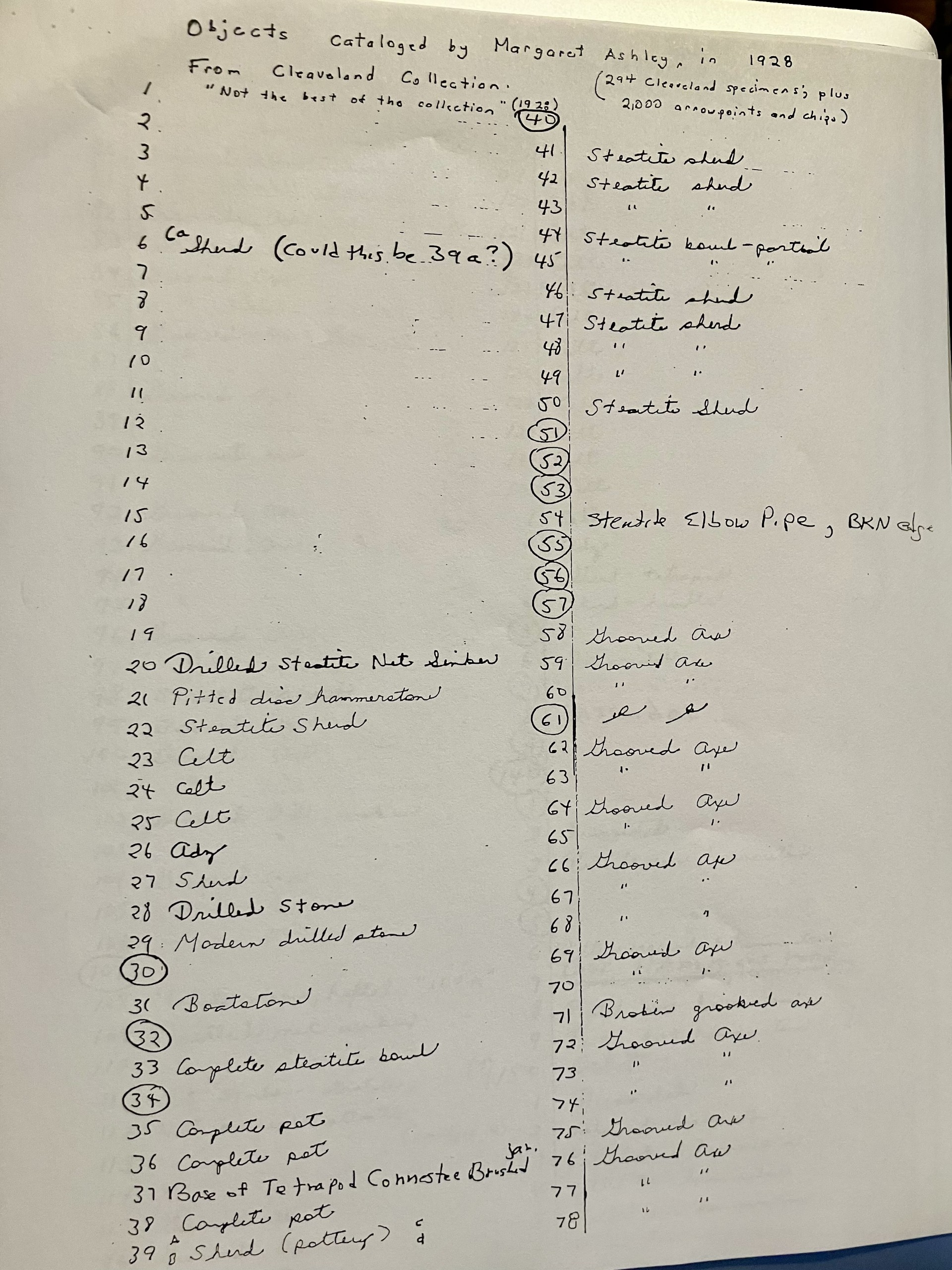

Accession records show Margaret receiving objects between July 10–20, 1928. On July 16 she accessioned between 33 and 400 objects from the Cleaveland Collection.

At the July 8 Trustees meeting, it was reported that although the Museum’s early work centered on biology, the arrival of Margaret and Miss Helen McCormack of the Charleston Museum would “scientifically establish” the archaeological department. By July 22 Margaret had catalogued 32 new specimens donated by individuals, as well as 294 items and more than 2,000 points and flakes from the Cleaveland Collection—not including the finest items. She pledged to return the following year to install the collection and to donate specimen cases for fragile pieces. She praised the Cleaveland Collection as “an excellent one,” representing nearly every type of artifact typical of Indigenous peoples in the region, and planned to publish an article about it.

In a July 29 letter to Foreman, she wrote:

“I have been quite busy the past two days with unpacking and copying the catalogue of the Cleaveland Collection in a new accession book. When I finish I will send it to Helen (McCormack). There is more work to be done on the material when it is installed, but that part must wait until next summer.”

At the August 12, 1928 meeting, Margaret was appointed to the Museum’s Advisory Committee alongside distinguished figures including Laura M. Bragg (Director, Charleston Museum) and Clifford Pope (herpetologist, American Museum of Natural History).

Minutes from August 26 record her report from the Department of Anthropology and a discussion regarding the preservation of local Indigenous sites. Thomas Harbison emphasized the significance of the Franklin mound, and the Trustees voted to support efforts to restore it as a state monument.

On June 22, 1929, Margaret wrote to Foreman: “I regret that I shall not be able to come down. My work here will keep me busy all summer.”

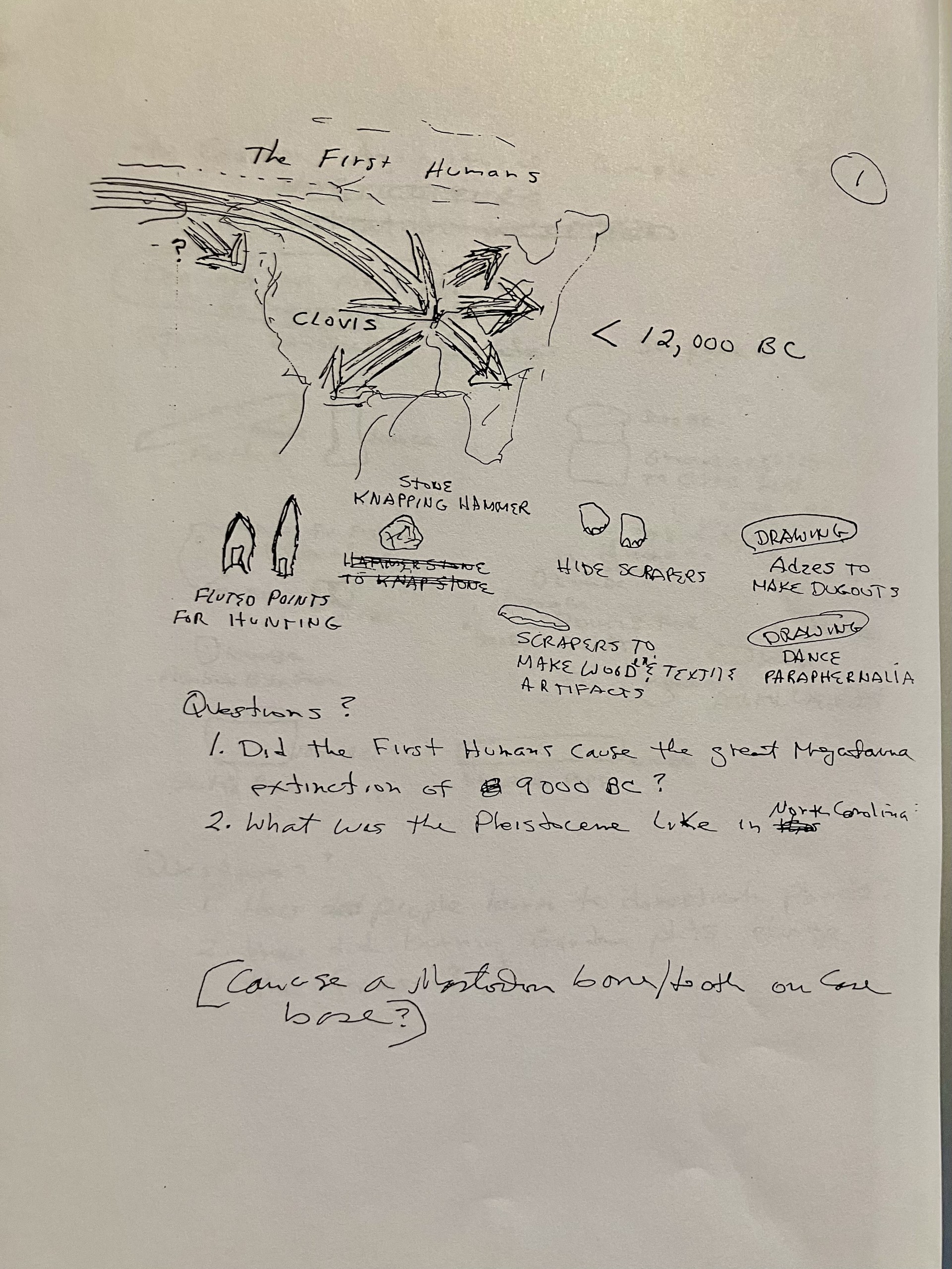

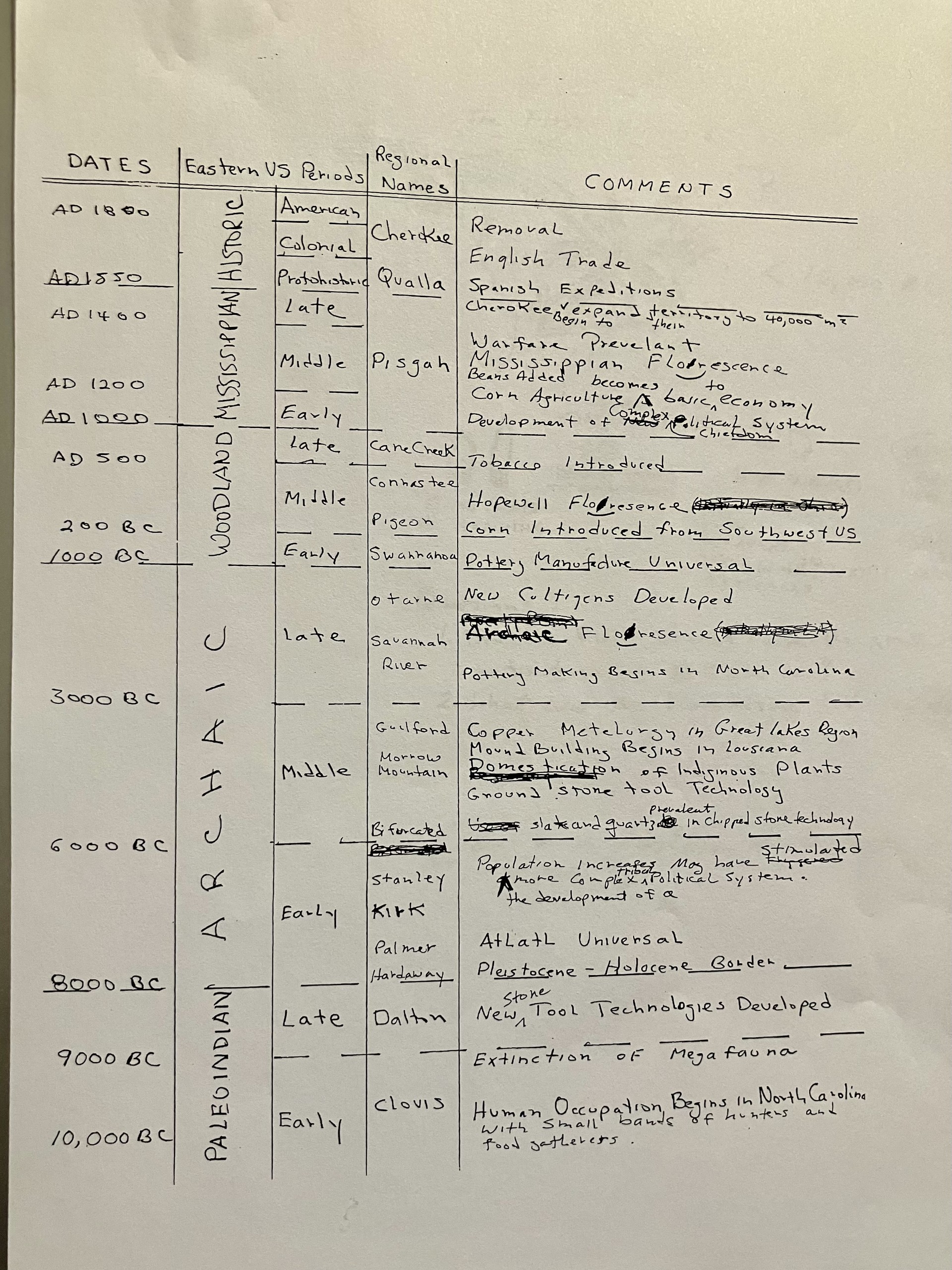

Margaret’s catalog of the Cleaveland Collection survives as a basic handwritten inventory, listing “294 Cleaveland specimens plus 2000 arrowhead points and chips – not the best of the collection 1928.” A four-page exhibit plan also survives and was partially implemented in the Highlands Biological Station (HBS) Nature Center.

Around 2000, the Cleaveland Indian Collection was re-cataloged by Dan and Phyllis Morse, although their listing has not been located. Most objects remain in bins with numbers; some are displayed at the HBS Nature Center and the Highlands Historical Society. HBS plans to have them cataloged again by faculty and students in the Western Carolina University Anthropology Department.

Margaret and Gerald Towle

Margaret met her future husband, Gerald “Jerry” Towle (1896–1944), in 1928 at the Etowah site. A Harvard graduate student, he served as Moorehead’s principal field assistant at Phillips Academy. In 1929 Moorehead appointed Margaret as a research associate in Southeastern archaeology. After another summer in Georgia, she returned to Andover with Moorehead and Towle to study Etowah pottery. In 1929 she also assisted Towle with excavations in Maine.

Towle, a 1919 Harvard graduate and WWI veteran, later joined Phillips Academy. The couple married on February 18, 1930. Their engagement announcement noted: “Both are intensely interested in archaeological research in which both have established national reputations.” They had no children.

By 1931—due to economic pressures, shifting politics, and challenges faced by married women in academia—both stepped away from archaeology for roughly fourteen years. (Even Moorehead left active fieldwork after 1930.) Margaret did not return to anthropology and archaeology until 1944, the year Gerald died by suicide.

Margaret’s engagement announcement in The Atlanta Constitution, November 10, 1929.

Margaret’s Return to Archaeology

After Gerald’s death, Margaret lived privately but immersed herself in volunteer work at the Harvard Botanical Museum. She occasionally lectured on Indigenous history, including a 1942 talk on “Indian Lore” at the New England Museum of Natural History. Beginning in 1948 and continuing for more than a decade, she published extensively on the ethnobotany of pre-Columbian Peru.

She re-entered Columbia University’s Ph.D. program and in 1958 submitted her dissertation, “The Ethnobotany of Pre-Columbian Peru as Evidenced by Archaeological Materials,” which was published in 1961. In 1962 Hugh Cutler of the Missouri Botanical Garden praised the book:

“Towle’s book not only fills a long need for a summary of useful plants of pre-Columbian Peru, but will aid anyone wanting to study plants today in fields and markets where Indian cultures persist, from Mexico to central Chile.”

By 1959 she was active in the Georgia Botanical Society, participating in discussions about a proposed 100-acre botanical garden at Stone Mountain. She continued to work without stipend at the Harvard Botanical Museum for the remainder of her life. She became a Fellow of the American Anthropological Association in 1961 and of the Linnean Society in 1970.

Childhood polio left her homebound in later years, but she welcomed students to her apartment for mentorship and instruction. Her foundational role in shaping the early Highlands Museum remains an important chapter in the history of women in science during the early 20th century.

For more detail on her archaeological work in Georgia, see Grit-Tempered (1999), which includes a selected bibliography of her publications.

— Bryding Adams, Volunteer Archivist, December 2025