Highlands Biological Station

2025 IE Projects

Each semester, students at the Highlands Field Site embark on hands-on research projects that tackle some of the most pressing ecological and conservation questions in our region. Guided by faculty and community mentors, these projects take students from rivers and wetlands to caves, forests, and laboratories, giving them the opportunity to apply classroom knowledge in real-world settings.

This year’s projects reflect the incredible diversity of both the Southern Appalachian landscape and the challenges facing its ecosystems. From monitoring bats in caves and wetlands, to investigating microplastics in rivers and wildlife, to studying amphibian reproductive strategies and river restoration after Hurricane Helene, our students are making important contributions to science and conservation while gaining invaluable field experience.

We invite you to learn more about each project below and to celebrate the curiosity, dedication, and impact of the next generation of scientists.

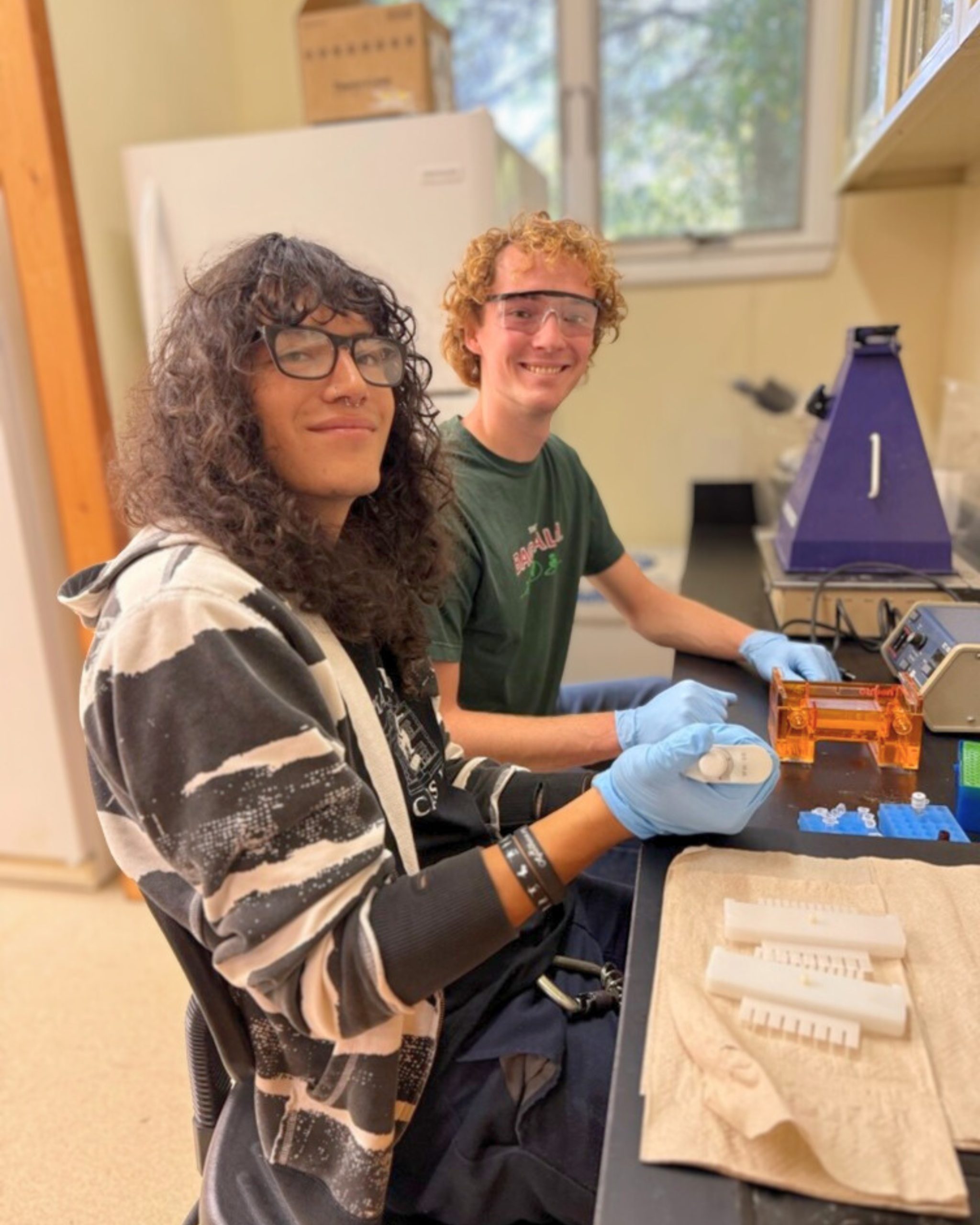

Alternative Reproductive Tactics in Blue Ridge Two-Lined Salamanders

Odell Escorcia-Puente and Stuart MacMillan, guided by Dr. Todd Pierson, explored the fascinating reproductive strategies of Blue Ridge two-lined salamanders. These amphibians exhibit two genetically distinct male morphs: “searching” males that court females on land and “guarding” males that remain in streams defending their nests. Odell and Stuart are investigating how annual shifts in weather patterns may affect the reproductive success of each morph. Their research provides new insight into how environmental variability shapes amphibian behavior and life history.

Photo by Rada Petric

Monitoring Bat Movement and Hibernation in Western NC

Across caves and mines in western North Carolina, Savannah Carter and Addie Melton monitored threatened and endangered bat populations. Working with mentors Dr. Rada Petric, Adriana Kirk, and Jason Love, they deployed acoustic and video equipment to study bat occupancy, movement, and hibernation patterns. Their findings will help inform conservation strategies for vulnerable species and ensure that these important insectivores are better understood and protected throughout their seasonal cycles.

Photo by Adriana Kirk

Bat Activity in Floodplain Wetlands of the Little Tennessee River

Wetlands are vital habitats, and this semester Yanira Rodriguez Mendez and Jordan Britt focused on their importance for bats. With support from Dr. Rada Petric, Adriana Kirk, and Jason Love, the students researched Northern Long-Eared Bats and general foraging behavior across six wetland sites in Macon County. After receiving specialized training in manual call identification with SonoBat software, Yanira and Jordan analyzed acoustic data to identify feeding activity, while also maintaining bat monitors in the field. Their work emphasizes how wetlands support biodiversity and highlights the challenges of studying wildlife in dynamic habitats.

Photo by Rada Petric

Water Quality in the Tuckasegee Watershed

In collaboration with the Watershed Association of the Tuckasegee River (WATR), students Parker Edwards and Jonah Ettore examined pressing water quality issues in the Tuckasegee Watershed. Mentored by Dr. Katie Price and Jason Love, they collected samples to test for E. coli, fecal coliform, optical brightening agents (OBAs), and chlorophyll a. Using handheld fluorometers for field analysis and working with NCDEQ and WCU for laboratory testing, their research helps pinpoint pollution sources and supports broader community and state efforts to protect water resources in western North Carolina.

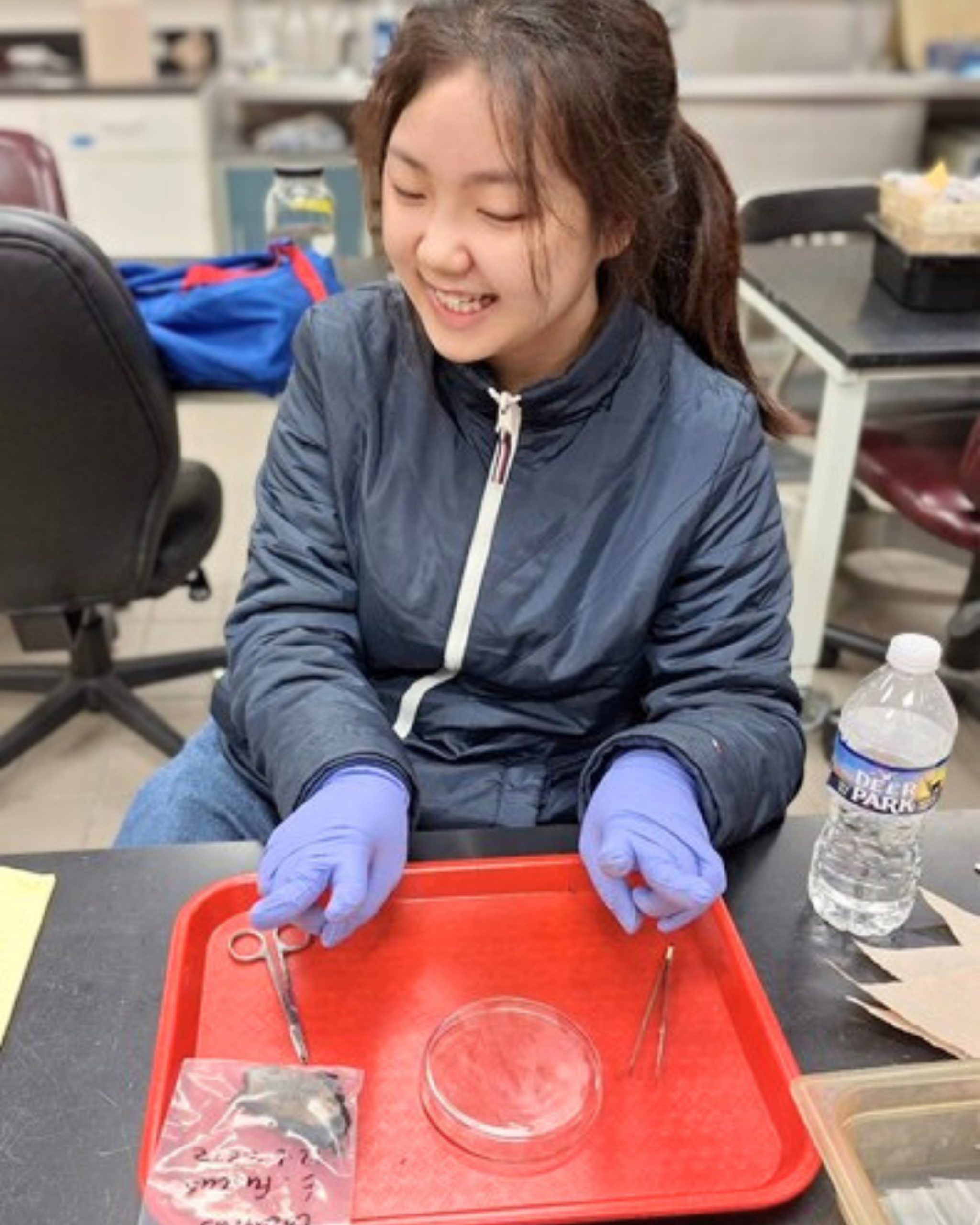

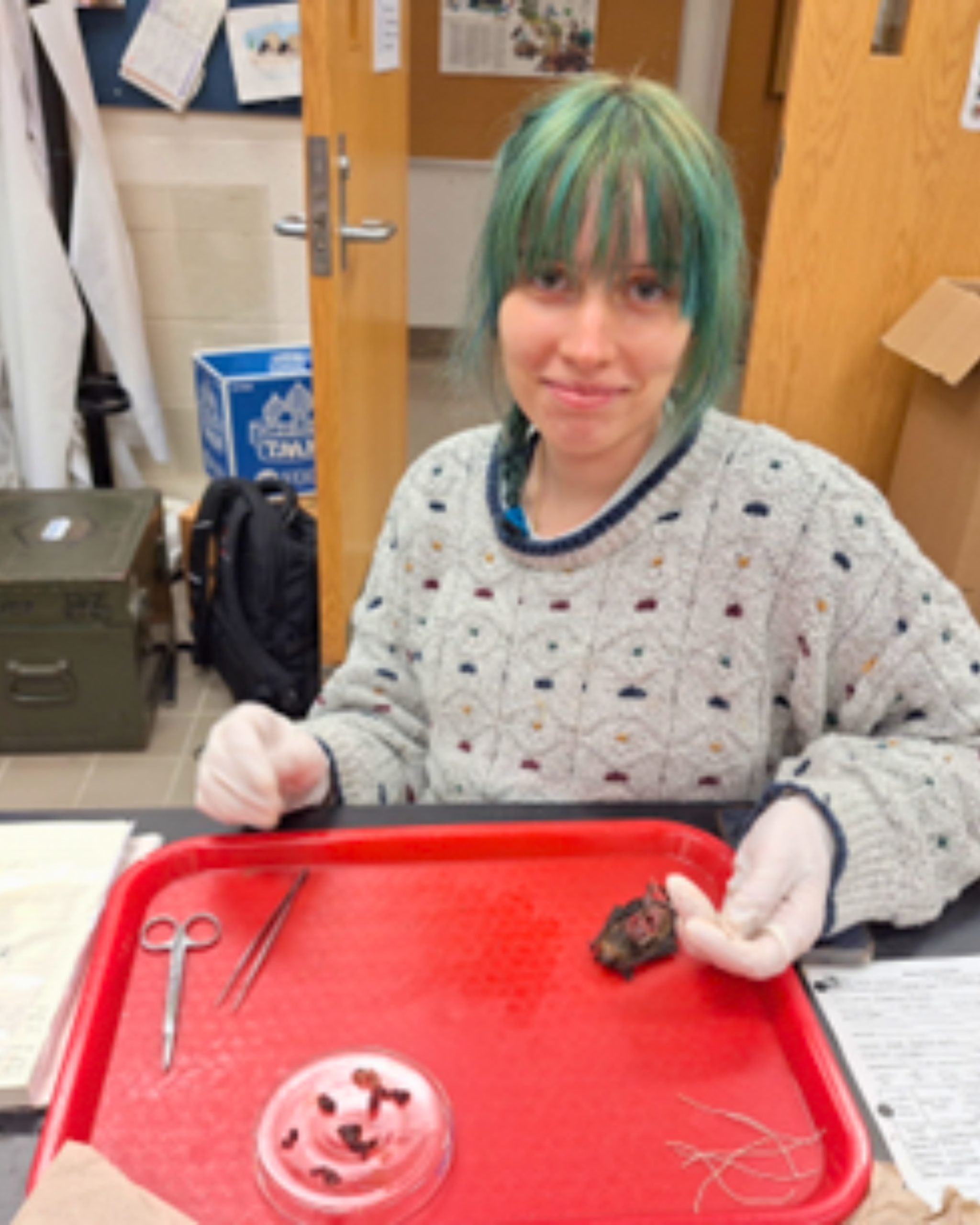

Microplastics in Bats Across Urbanization Gradients

Yuguo Tan and Rachel Price studied how urban environments influence wildlife exposure to pollutants by analyzing microplastics in bats. With mentorship from Lisa Gatens, Dr. Rada Petric, Dr. Austin Gray, and Jason Love, they examined specimens collected across a range of urbanization levels. Their findings contribute to broader conversations about urban ecology, environmental health, and the hidden impacts of human activity on native wildlife. This project underscores how contaminants such as microplastics can ripple through ecosystems in unexpected ways.

Photo courtesy of Lisa Gatens, North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences

Large Wood Survey in the Little Tennessee River

After Hurricane Helene, the Army Corps of Engineers undertook cleanup projects in the Little Tennessee River Watershed, removing trees and woody debris from streambanks and channels. Students Olivia Dail, Charlie Bowers, and Gray Hamby, with guidance from Jason Love and Dr. Keith Gibbs (WCU), measured and compared large wood volume and canopy cover at both managed and unmanaged sites. Their research will shed light on how wood removal affects stream habitat and ecosystem resilience, balancing the needs of flood mitigation with the ecological importance of instream wood.

Photo by Rada Petric

Surveying Macroplastics in the Little Tennessee River Watershed

This semester, Lawrence Weindorf and David Utz investigated macroplastic pollution across the Little Tennessee River Watershed. At four sites along the Tuckasegee River, the Little Tennessee River, the Cullasaja River, and Cartoogechaye Creek, the students used view buckets to locate and collect trash. Each item was then sorted by material and color to better understand how larger plastics contribute to the growing challenge of microplastic contamination in our waters. Their work highlights how local rivers connect to global issues of plastic pollution and watershed health.

Photo by David Utz

These student research opportunities at the Highlands Field Site are made possible through the generous support of the Highlands Biological Foundation (HBF). By investing in the next generation of scientists, HBF provides essential resources that allow students to engage in hands-on fieldwork, connect with mentors, and contribute to conservation and ecological understanding in the Southern Appalachians.

We are deeply grateful to the Foundation and its donors for sustaining a legacy of discovery, education, and stewardship at Highlands Biological Station.